Masahiro Miwa Festival - Purified Night

ぎふ未来音楽展2020 三輪眞弘祭 −清められた夜−

Purified Night

A Clean Society

As I write this in June 2020, I am preparing for a concert scheduled for September 19 at Salamanca Hall in Gifu city. This project was planned last year, but since then, with the sudden changes brought by the current pandemic worldwide, it has become impossible to predict whether we will even be able to hold the concert as scheduled. Therefore, we have scrapped the initial plan and changed to an online concert format without a live audience. The following is the current proposed promotional text for this concert:

Masahiro Miwa Festival - Purified Night -

In the first half of 2020, the unforeseeable coronavirus halted the progress of artists and music halls and forced most music performance venues to move online. In the post-coronavirus era, when artists can no longer enjoy music in the same space as the audience, which used to be the norm, how can music be sustained in society? Will this fundamentally change the future of music? Is there light at the end of the tunnel for music?

To question this state, which can be called “the end of the end of music,” in Japan and across the world, I will hold an online “wake for music by music” without a live audience and broadcast it from Salamanca Hall in Gifu city. Ockeghem’s Requiem will be performed by artificial voices with a pipe organ, considered the altar of Western music, and “the radio from the spiritual world” will intercept the voices of the dead. With my new piece that will be presented at this concert, Niwatoritachi no tame no gobōsei (Pentagram for chickens), I expect to make the online audience feel that they are present at a secret ceremony to mourn art by humans. The world depicted by the Miwa+Maeda monologue opera “The New Era,” published in 2000, and presented again 17 years later, seems to have now become a reality.

This event will be co-hosted by the Institute of Advanced Media Arts and Sciences (IAMAS). Thanks to the collaboration with this research and education institute that continually pursues the fusion of advanced technology and art, the usual audience at Salamanca Hall, as well as various other people worldwide, will bear witness to this one-night-only event as terminals on a network system.

Since the pandemic, various concerts, including those at live music clubs, have been forced to move “online.” However, I have long distinguished between musical experiences at live performances and those through “replication by a device,” such as CDs and broadcasts, naming the latter roku-gaku (a portmanteau suggesting “recorded music”). I believe that the online expression of music cannot be considered “music” in the first place. However—and I often make particular note of this—I do not, therefore, claim roku-gaku is terrible or worthless; honestly, I believe it to be something different from music. Furthermore, my interest until now has been exclusively in “music,” that is, in the experience of music created when live performances and the audience “share a common time and space.” However, if traditional live music performances are no longer feasible or permitted, and if this is how our future will be, is my only choice to stop creating music? The phrase “the end of the end of music” used in the proposed promotional text indicates the sense of crisis that I feel.

What shocked me the most about this pandemic was not “the size of the damage” caused by it—its scale, number of deaths, or effects on the global economy—but that people worldwide consented to the prohibition of group religious worship and proper funerals for those who have died from the virus. Unlike in earlier times when we feared infections, considering them “the work of the devil,” our current ability to identify the new virus as the cause of infection and predict its fatality rate and spread with computer simulations, based on advances in not only medicine but also statistics and mathematics, should have reassured us considerably. However, we have sacrificed “religious worship and funerals” in exchange for safety by relegating them as “not urgent and not necessary.” This proves that we have transitioned from a world containing something more precious than human life itself to one that has nothing of the sort. It means that we have deemed the virus to be the “enemy” and have determined that protecting people from the virus is more important than paying respect to the dead.

At a certain lecture meeting, I said something along the lines of “art was born when humans began to bury the dead with consideration.” I cannot forget the person who approached me after the lecture and said, “I reckon I’ll just get them to throw me out in the garbage when I die.” I suppose that the person wanted to rebut my assertion, but I believe that a human world without religious worship and funerals would be a rational, “clean” society. It would be a world without any trace of the souls of the dead, and without a future to leave “my” wishes to , populated by mere flesh-and-blood humans imbued with knowledge.

Moreover, I believe that the range of online services available on the Internet is what suddenly accelerated this situation. Having experienced online meetings, classes, and even drinking parties, humans have now happily learned new ways of “meeting others without actually meeting others.” This also applies to video broadcasts of music. This could be considered the trigger for everyone around the world to establish themselves as “a network terminal.” As smartphones are already akin to our body parts and can be considered “expanded cognitive organs,” a “hybrid ecosystem of machines and humans (life)” is being developed on Earth. It is obvious that “cyborgs” who are constantly connected as terminals to a global-scale network would have no privacy (respect for individuality). If some people have the privilege to use such virtual information, a complete surveillance society will emerge instantly. I am aware of states that have actually already achieved this. We will soon witness the arrival of a “clean” society without any secrets, which can allow people to reveal evidence that a certain person committed an offence or to prove that they did not.

A “clean” society would be an equal society founded on scientific evidence, without discrimination. This is because before mechanical systems, all people are identical. To a machine, the noblest of characters and the vilest of people, or the loftiest of intentions and the darkness of a warped mind, are of equal value. This kind of society would be, as I mentioned above, a world that has nothing more precious than human life. Individuals would be considered a collection of measurable and predictable “individual information” of all kinds—preferences, medical history, risk of cancer, asset and liabilities, purchase history, and movement history—and it would undoubtedly become an existence managed and evaluated by technology. If humans seek to maintain a capitalist system that assumes unlimited economic development, this would be essential.

(June 2020, Miwa Masahiro)

A Pentagram for Chickens (2020)

Watching videos from other countries on the burial of the many who have died due to this pandemic reminds me of the recent avian influenza and swine fever. If a bird infected with the avian influenza virus is discovered in a chicken farm, all the birds around it are “disposed of.” The multitude of corpses are buried in a big hole, and white disinfectant powder is spread liberally over them as in these images. As there is nothing more precious than human life, these human acts must all be rational and “correct.” If this is the case, has the word “cleanse” come to mean “disinfect” with white powder (probably slaked lime) and maintain a “clean” society for those of us living in the modern age?

(Although I am not a Christian) I am reminded of the following verse:

Jesus reached out his hand and touched the man. “I am willing,” he said. “Be clean!” And immediately the leprosy left him. (Luke 5:13))

Even Jesus had to face the sick man who anyone at the time would have feared to approach, let alone touch, to dispel leprosy. Of course, we have no hope of working such a miracle. However, have we reached a point where the “irrational” emotion that leads us to think that this event is beautiful and drives us to look for miracles is something that should be derided?

-Formant Brothers: Spirit World Radio + Boi-Pa and Umi Yukaba (2020)

Since ancient times, things that link nature and society, like livestock and poultry (chickens), technology and machinery (mirrors and comma-shaped beads), and the arts (the goddess Ame-no-uzume), have been said in Japan to enable restoration from death to life (from dark to light) through ceremony (dedication). The spirit fostered by these kinds of myths concerning their own origins must have been shared in various forms by Japanese people—no, by people from all cultures, essentially. I also feel that they are still being uncovered in unexpected forms today. While humanity’s “ignorance” may be suppressed to the limit before the overwhelming “correctness” of our own reason, it cannot be wiped away, rationalized, or completely made “clean” as long as we remain “human.” If that is so, how should we understand the existence of humans living in modern society with its assumption of advanced technology? I have been thinking about these sorts of things through the activities of the Formant Brothers, the unit I formed with Nobuyasu Sakonda to work on the phenomenon of “voice” through “speech/song” using artificial voices.

The experience of hearing “voices” rather than “sounds” lies in the realm of cognition that precedes the operation of human reason. This is an almost physiological truth that supports the key premise of “being human” at a more primitive dimension than the human “mind” in religion, myth, and all the other elements of culture throughout time and space, let alone reason.

For example, the Formant Brothers’ assertion that “humans cannot hear a certain aural phenomenon as both a voice and a sound at the same time” means that all aural phenomena that enter our ears are either a voice or not, a decision made by our bodies, not our reason. This is why we can only hear voices, rather than listening to them. The Formant Brothers also assert that “the voice is not ‘a boat to carry language’.” Besides linguistic meaning, the boat also carries the “breath” of sexual love, of insanity, or of pain from illness, for instance. What is more, it is precisely the texture and grain of the “boat” (= the voice) itself that becomes apparent (to me) before any “meaning.” In other words, the moment we hear a certain “voice,” we cannot help but directly observe the other (the entity) that emitted the voice as though it was immediately before us—even if the “voice” is clearly an unnatural, artificial aural phenomenon.

Monju-Bodhisattva Speaks for Koto and a Wind Bell (2019)

Amid these experiences, the Formant Brothers have recently been thinking about the act of “chanting.” If the purpose were linguistic “understanding,” silent reading would suffice, but humans have always chanted sacred writings or spells “out loud.” The fact that these are often stylized in unique forms with long, stretched out pronunciations distinct from everyday utterances should be obvious if you recall Gregorian chants in Christianity or Buddhist liturgical chants. I feel that this is exactly where “songs” find their origin, and the same thing can also be found in the charms that children chant with formalized intonations, such as “engachokitta” (a Japanese charm used to prevent catching “germs” from others) . Even so, can charms only be chanted by humans?

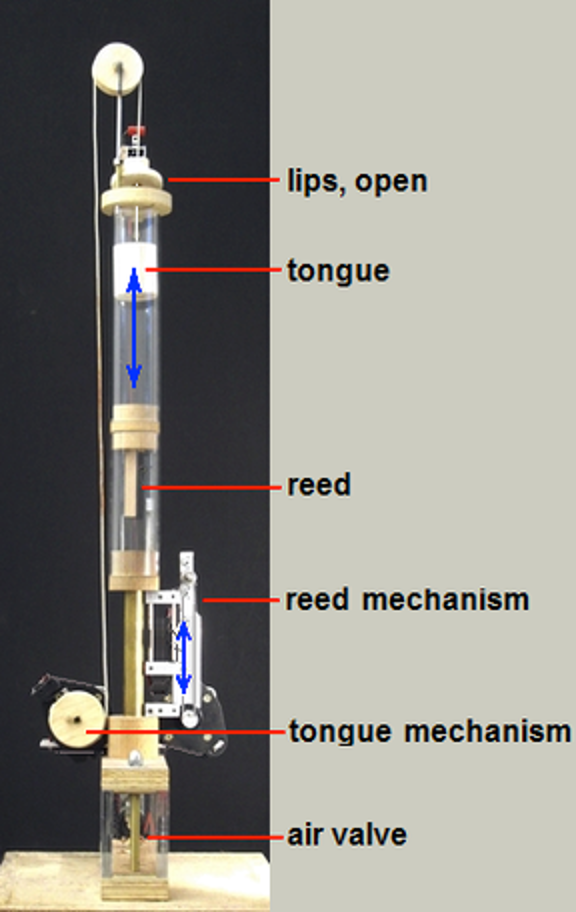

In hitonokiesari: Introduction and Recital of a Poem by Sadakazu Fujii for Singing Machine, Ein Ton and Nine Players (2013), which was named for a line of a poem with seven stanzas of seven lines with seven hiragana characters each, I attempted to recite a poem using the “Singing Machine” created by the artist Martin Riches. Having realized this, Monju-Bodhisattva Speaks (2019), which is to be presented again, is a work in which humans chant the same poem, which could be considered a lament for the dying human race, in a way that imitates the “speech principles” of this device. However, the human wearing head-mounted display (HMD) is in augmented reality. In this way, all that is left on the earth are the “voice” of cyborg-like human and the sound of the koto, as well as the echoes of windchimes, like “a recitation of sadness” (from Sadakazu Fujii’s lyrics) in a virtual space.

Singing Machine (2013) by Martin Riches

Johannes Ockeghem: Missa pro defunctis (organ and two MIDI accordion version) (fifteenth C.)

Johannes Ockeghem lived in the fifteenth century when the Black Death was prevalent, taking about half the population of Europe as its victims after appearing in the mid-fourteenth century. He could hardly have imagined that the mass that he composed would be “chanted” by artificial voices and broadcast on the Internet several centuries later. However, I believe that as long as humans are “performing” after much rehearsal, as they would have at the time, the fact that humans “chant” the text of the requiem still holds.

Incidentally, the venue for this concert, Salamanca Hall in Gifu, has a large pipe organ. The New Cathedral of Salamanca in Spain, which commenced construction about when Ockeghem composed this mass, had an old pipe organ dating to the Renaissance; features from this pipe organ were incorporated into the organ in Salamanca Hall in its manufacture. It is the so-called “altar” of the hall. Nevertheless, there is a large difference between the two organs: while the organ in the Spanish cathedral is used for religion, the organ in the Gifu hall, which could be considered a transplant from the older instrument, is used for the arts.

The many pipe organs that have been installed in concert halls around the world in modern times are purely “instruments,” completely separated from Christian belief (that is, churches). This symbolizes the end of religion and the beginning of the arts, or in other words, the separation of art from religion, in early modern Western history. Moreover, am I the only one who feels that the “state-of-the-art” technology at the time these instruments were manufactured laid the foundations for the world that was to follow, without excess or omission? To put it another way, “organs” were literally oriented toward “organization” through machinery. Were they not made with the intention of mechanically realizing something that encompassed every known thing, a certain type of universal machine? In the sense of encompassing all other instruments, they are “the alpha instrument,” and this intention is shared by modern computers, which were devised as all-purpose computing machines.

Now, what performance can we expect from the sculpture in the image of an angel holding three mute pipes among the 3000 pipes in Salamanca Hall? By being present at a joint performance by this pipe organ and “voices” synthesized using modern digital technology, which does not produce any droplets of saliva, I wanted to stay up to witness the demise of Western arts, not to mention religion.

Purified Night

When naming this event “Purified Night,” I had in mind “Verklärte Nacht” (Transfigured Night), a string sextet composed in 1899 by a young A. Schönberg. I believe that this piece is a landmark in Western musical history, but contrarily, it was also a junction in the history of humanity leading to a world “without a future.” Naturally, the “future” included the twelve-tone technique that Schönberg himself would invent, but this means that the world predicted by this technique has now become reality. This is the world with music in which (the distortion between) each musical interval has been regularized by even temperament and all tonic hierarchy in the scale has been removed and “equalized,” that is, the contemporary world.

In this world, I have come to feel a desire to cast a “charm” to “purify” the innumerable animals that have been “disposed of” due to the many recent epidemics that I mentioned earlier—I have come to feel a need to do this, if I am “human.” Then, I thought that the outlook on the universe developed by gamelan music while humans previously intertwined their own fates with those of plants and animals on this Earth would be suitable for chanting this “charm” at a “vigil” where we stay up to witness the demise of human music, because now, this appears to me like a jewel for telling our future, as traces of “something that humans could also have been, not something they had to be.” The “voice of nobody” provided by the rebab, the only string instrument used in gamelan, is sure to sing something for us there. I also intend to dedicate the entire performance to “the spirits of chickens,” because “charms” can only be chanted outwards from the human world—from the “system” that we reside in.

The Divine Melody + The Shooting Star Worship (2020 version)

However, after this “vigil,” will the sun rise again? It may be true that dark nights have always been followed by the sunrise so far, but “staying up for a vigil” should only make sense if we assume that “people sleep at night.” Are we really sleeping today? As smartphones have become part of our bodies as an “expanded cognitive organ,” we have begun to exist as “terminals” of a global digital network, (which is only a recent development). Just as we no longer turn off our constantly connected smartphones on the assumption of an unending electricity supply, perhaps we too have started living in a continuation of time that is merely stretched out without night, like a power-saving nap state that is “sleep mode.”